PLACE RUPTURE: A PHENOMENOLOGY OF SUBURBIA

Suburbia has failed. The pseudo-pastoral ideal of the Georgian mercantile elite has given rise to a selfish, introverted landscape—decentralised, homogenised and adulterated. The need for intervention is imperative. Such intervention can only proceed with a fuller, holistic understanding of the suburban paradigm. This presentation advances phenomenology as a method for acquiring this insight.

A Phenomenology of the Residential Suburban Street (Author's, 2020)

A PHENOMENOLOGY OF THE RESIDENTIAL SUBURBAN STREET

Our residential streets—the bone and marrow of our lived-in landscape—are being eroded visually and experientially by profit motive, the whims of individuals and the pace of change at every level (population growth, climate change, traffic volumes, light, air and noise pollution etc.). One might propose a measured, positivist response—systematically identifying the threats and formulating new innovative strategies. However, even if we design the most efficient system within which to design and operate we will not conduct ourselves like ants or bees; we will continue to impose upon the landscape any number of deleterious accretions, oblivious to—or in spite of—their wider impact. We have given rise to selfish landscapes, wherein the built form of modernity—to borrow a phrase from Peter Buchanan (2012:137)—‘manifests itself in a hyper-individualist orgy of indulgent and shallow “creative” self-expression’.

Ian Nairn (1956:365) wrote not of suburbia but a ‘creeping mildew […] that circumscribes all of our towns’—a ‘subtopia’. Such anger and cynicism is grounded in experience. The suburban streets are understood through the worlds of the people who use them and not abstract scientific hypotheses alone. It is this holism that phenomenology seeks to capture. This dissertation rejects an abstract, positivist approach to the suburban problem and reinstates embodied experience as a vehicle for its understanding and change.

Theoretical Terrain: Husserl and Heidegger (Author's, 2020)

THEORETICAL TERRAIN

Phenomenology assumes, firstly, that subject and world are intimately connected and secondly, that the manner by which we study the world therefore necessitates a ‘radical empiricism’ by means of an embodied, immersive participation by the researcher (Seamon, 2002:9). Phenomenology’s conceptual and methodological foundation is rooted in the work of Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) who claimed ‘we must go back the “things themselves”’ (Husserl, 2001:168), that is, back to the ways things are given in experience in their pre-scientific state.

Phenomenology renders explicit the indivisible nature of body, world and other (subjects, entities, memories, affections etc.). This undissolvable unity is what Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) called Dasein. A fundamental structure of Dasein is Being-in-the-world [In-der-Welt-sein] (Heidegger, 1962:65). Whilst we are immersed in this world, most of our being occurs unselfconsciously—it has a ‘pregiven, taken-for-granted character’ (Moran, 2014:29). It is this realm of ‘ignored obviousness’ (Zahavi, 2019:67) that phenomenology seeks to explore.

For David Seamon (2002:5), Lifeworld [Lebenswelt], place and home are three key phenomenological concepts because ‘each refers to a phenomenon that, in its very constitution, holds people and world always together’. In summary, Lifeworld is the ‘tacit context, tenor and pace of daily life to which normally people give no reflective attention’ (ibid.), whilst place and home are dimensions of the Lifeworld in which we bind ourselves physically and emotionally.

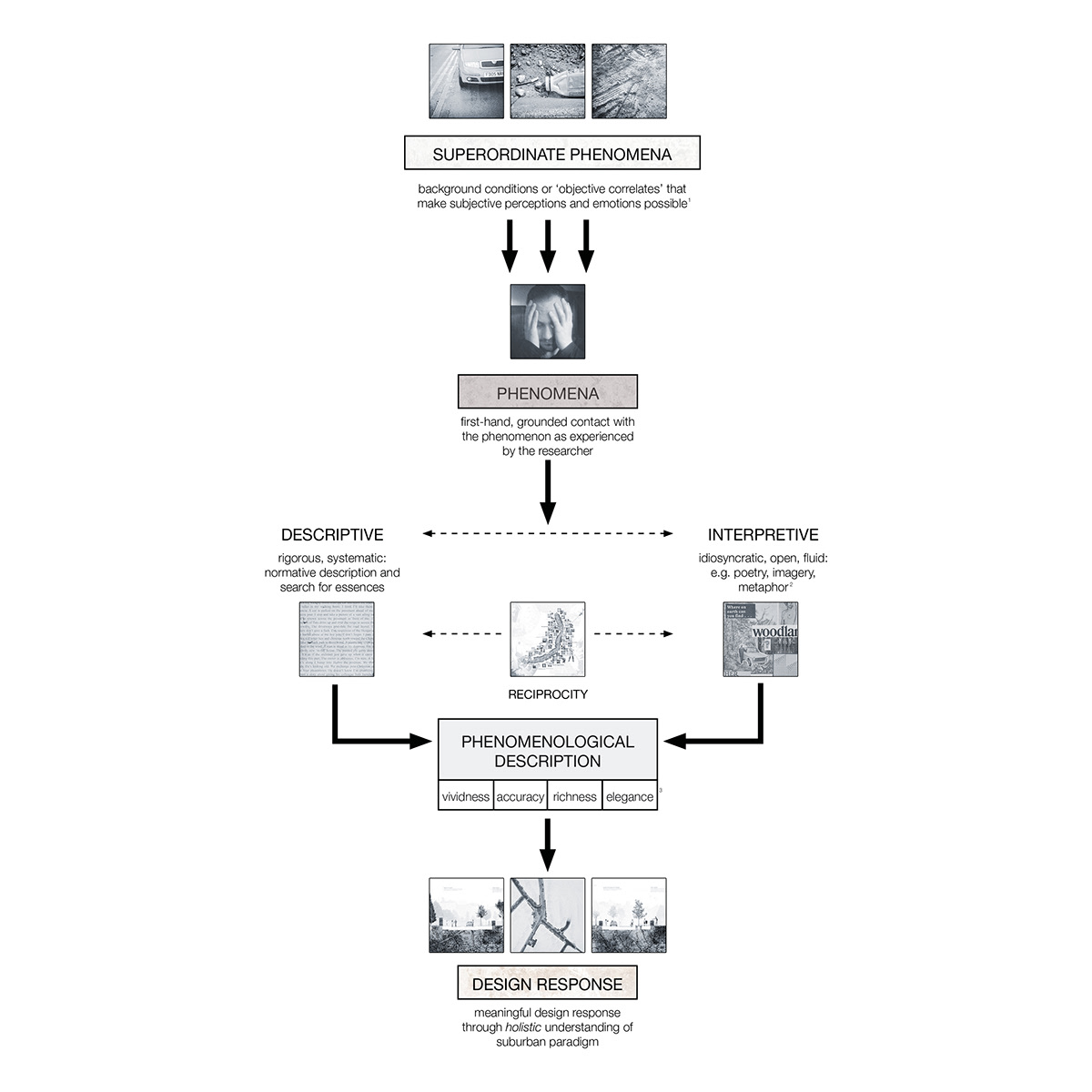

Methodology (Author's, 2020; after (i) Broggi, 2018; (ii) Finlay, 2009; and (iii) Polkinghorne, cited in Seamon, 1987).

METHODOLOGY AND RATIONALE

Descriptive phenomenology assumes a position close to Husserl and seeks sincere pre- and a‑theoretical accounts of phenomena as they are given and then looks for their general or essential structures. Post-Husserlian thinking has extended and transformed the phenomenological enterprise. Interpretative phenomenology ‘focuses on rich, thorough descriptions of lived experience that unfold via an engaged openness to the phenomena’ (Seamon, 2019:38). For Linda Finlay (cited ibid.:39), most phenomenological practice falls ‘somewhere in between’.

Interpretative phenomenology is a comparatively fluid, artistic, ideographic analysis, which challenges and reverberates with the researcher’s lived experience. In a landscape design context, phenomenological methods can be used to engage with the site and draw out its intangible dimensions. Moreover, as an ‘insider’ the researcher is uniquely positioned to elaborate upon the lived dialectics of place (e.g. inside-outside, movement-rest, home-reach).

The nature and meaning of place are integral to the phenomenological notion of the ‘everyday’—our taken-for-granted relationship with objects and events. Anne Buttimer (1980:170) elaborates: ‘The meanings of place to those who live in them have more to do with everyday living and doing rather than thinking’. The transient, technological post-War suburb, which has been suppressed by fifty years of Modernist rhetoric, is contrary to the formation of place. A phenomenological approach to suburbia presents opportunities to better understand place and place-making and may indeed be instrumental in the recovery of place.

The Age of the Restless Machines (Authors, 2020)

PHENOMENOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

Horrigan-Kelly et al. (2016:4) write: ‘while Heidegger did not make clear a method for phenomenological research, his focus on interpretation has facilitated a variety of interpretive research methods to reveal and express the human experience’. Thus, visual and linguistic media (poetry, prose, collage, digital montage) were employed to engage with the street and broaden the author’s field of vision. However, a description of the world by those immersed in it does not automatically qualify as phenomenological. A purely descriptive phenomenology devoid of systematic ambitions, for instance, has been dismissed by critics as ‘mere “picture-book phenomenology”’ (Zahavi, cited in Seamon, 2019:38).

Horrigan-Kelly et al. (2016:4) write: ‘while Heidegger did not make clear a method for phenomenological research, his focus on interpretation has facilitated a variety of interpretive research methods to reveal and express the human experience’. Thus, visual and linguistic media (poetry, prose, collage, digital montage) were employed to engage with the street and broaden the author’s field of vision. However, a description of the world by those immersed in it does not automatically qualify as phenomenological. A purely descriptive phenomenology devoid of systematic ambitions, for instance, has been dismissed by critics as ‘mere “picture-book phenomenology”’ (Zahavi, cited in Seamon, 2019:38).

The challenge, then, was to remain phenomenological, that is, maintain an openness to phenomena, whilst suspending or ‘bracketing’ one’s preconceptions and prejudices. Notwithstanding this, the ‘anger and cynicism’ that motivated the research is evident throughout, not least in a series of paper collages which draw upon the creative impulses of the subconscious. The Age of the Restless Machines (above) necessarily abstracts from the ‘reality’ of site by combining material from an unrelated source. It is nonetheless a fluid and poetic means of expression that helped to elucidate phenomena and concretise the apparent failure of suburbia posited by the author.

A Circular Walk in Suburbia (Author's, 2020; using Google Earth Street View and EDINA Digimap aerial photography).

PLACE RUPTURE: SUBURBIA AND THE EVERYDAY

Consciousness is the means by which we become aware of things—both real (material and biological entities) and ‘irreal’ (non-sensory entities such as numbers and ideas) (Giorgi et al., 2017:178). One of Husserl’s central concepts is ‘intentionality’, or the ‘world-directedness of consciousness’ (Zahavi, 2019:27). In her first-person account of chronic progressive multiple sclerosis, S. Kay Toombs (1995:19) movingly describes the ‘frustration of intentionality’ through her inability to perform certain tasks and her dependency on others. I do not draw parallels between Toombs’ embodied existence and my own (I can navigate a car blocking my path with comparative ease), the frustration of intentionality, however, resonates. My intentionality, then, might be directed toward a specific object or event (the aforementioned car, perhaps) or, more broadly, quieter, safer, friendlier streets.

In its ordinariness the residential suburban street might be said to epitomize the quotidian Lifeworld. A user/resident’s relationship with the street is not merely spatial or temporal but radiates meaning that derives from experiences, memories and affections. When these experiences are undermined we become detached from place—our taken-for-granted existence is disturbed such that we abstract from reality (reflect, theorise) in order to question and understand this disruption. One might, for example, reflect upon the suburban paradigm because it is—phenomenologically speaking—defective or ‘broken’. Here, the taken-for-granted ‘everyday’ of the street is ruptured by experiential intrusions (a car blocking the path, a burglary, litter, aggressive driving etc.). These are the superordinate phenomena or ‘objective correlates’ (Broggi, 2018:26) that make subjective perceptions and emotions (anger, cynicism, disdain etc.) possible. The overriding objective, then, is to resolve this ‘place rupture’.

Regional Context and Phenomenologically Orientated Masterplanning (Author's, 2020; using EDINA Digimap aerial photography).

REGIONAL CONTEXT AND Phenomenologically Orientated Masterplanning

A first-person interpretative phenomenological enquiry draws on the realm of experience closest to the researcher—their own lived situation. Priest’s Lane in Brentwood, UK is representative of both the suburban residential street and the place in which the author lives. The choice of a site familiar to the author has relevance phenomenologically because ‘we first of all understand the world through the equipment and practices within which we dwell’ (van Manen, 2007:17).

Brentwood remained relatively isolated from London’s sprawl until the coming of the railway (1881) and ensuing development around the new commuter hubs (Brentwood Station and the neighbouring Shenfield and Hutton Junction). The post-War period saw the arrival of new housing typologies which ‘filled the gaps’ and extended the urban footprint. This, coupled with the ‘individualisation’ of property (Edwards, 1981:208) and an exponential rise in car ownership, fundamentally changed the built form and aesthetic of town, suburb and street.

At Masterplan scale, emphasis is placed on three main transport corridors (M25, A12, railway) which sever Brentwood from surrounding farmland and municipal parks. Attention is drawn to this ‘zone of severance’ and to the fragmented nature of Public Rights of Way (PRoW). PRoWs have relevance phenomenologically because we understand our world as embodied, bipedal subjects. The four-lane motorway which residents must cross to access farmland to the north, for instance, represents a ‘restrictive potentiality’ (Toombs, 1995:11) for their bodily existence by undermining their taken-for-granted passage of movement, and by effecting certain subjective emotions (anxiety, discomfort etc.).

Regions of Home and Horizons of Reach (Author's, 2020)

REGIONS OF HOME AND REACH

A phenomenology of the residential suburban street necessarily reaches beyond the site’s geographical extent—one cannot put a box around lived experience. Anne Buttimer’s (1980) notion of ‘home and reach’ is instructive in understanding the range of everyday embodied existence. The study area is within what the author has termed a ‘zone of severance’, wherein physical and experiential reach is curtailed by major transport infrastructure. This in turn has profound impact on lived dialectics of movement and rest. This phenomenon was acutely apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic when driving to access places further afield (Weald Park or Thorndon Park, for instance) was prohibited. At this time, semi-rural land around Hall Lane was walked extensively, indeed, was readily integrated into the author's ‘home grounds’.

The empirical notion ‘how many metres is it to the park?’ is relevant, but of greater interest to the phenomenologist is what lies between here and the park (physically and experientially)—what ‘potentialities’ exist in that space (Toombs, 1995). Strategies to safely negotiate the A12 to access farmland at Canterbury Tye were thus proposed to extend the user/residents’ horizon of reach and mitigate the ‘restrictive potentialities’ alluded to above.

Haunted Victims of the (Sub)Urban Milieux (Author's, 2020)

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT

One of the central ambiguities of the residential street is the semi-detached dwelling. Homeowners soon undermine the visual control of the architect with their own alterations and ornamentation. Thus, one building, designed in the architect’s vision, is corrupted. For Richard Sennett (2018:280) design interventions which rupture the existing suburban fabric tend to be ‘power boasts’. Until the semi-detached is acknowledge as part of an architectural ‘whole’ the suburban street will be forever subject to ruptures in built form and aesthetic.

In the conceptual montage (pictured), image-making migrated from the analogue into the digital realm, drawing on multiple visual resources and creative impulses. Ultimately, the image pines for a landscape that remains in the realm of fantasy. It is nonetheless a powerful statement on both problems inherent to the street (semi-detached houses carved into two by the respective agendas of their owners); and the dream of a better environment—here with reinstated gardens and hedgerows, a ‘fietsstraat’-style cycleway, and a mythical absence of motorised traffic. The sentimentality inherent to this image is captured by Buttimer (1980:166), who writes: ‘nostalgia for some real or imagined state of harmony and centredness once experienced in rural settings haunts the victim of mobile and fragmented urban milieux’.

Design Proposal: The Living Street (Author's, 2020)

DESIGN PROPOSAL: RECONCILING PLACE RUPTURE

The design proposal aims to optimize the health, well-being and ‘liveability’ of the suburban realm by respecting and enhancing physical, ecological and human (physiological, psychological and phenomenological) systems. The strategy is multilayered and draws on the ‘Fietsstraat’ (cycle boulevard) and ‘Woonerf’ (living street) philosophies, which have precedents on the Continent (notably the Netherlands and Germany). Whilst comparatively subtle, these interventions respond to the phenomenological analysis by addressing the author’s notion of ‘place rupture’. The ‘restrictive potentiality’ of a car blocking a user’s path, for instance, is addressed by prioritising cycling and pedestrianism. Here, anti-social parking is disincentivised through legislation (a blanket ban) and a collective sense of responsibility enabled by positive ‘place processes’ (Seamon, 2014).

The chosen intersection demonstrates a range of existing and proposed landscape typologies. Here, the veteran oak (Quercus robur) is retained as the central feature of a Woonerf-style shared space. A Fietsstraat, meanwhile, connects the Elizabeth Line (Crossrail) at Shenfield with Brentwood town centre, residential zones and schools. The central tenet of the Fietsstraat is that the car is a ‘guest’. The Fietsstraat remains an active transport route, but motorised traffic is obliged to yield to cyclists and/or find alternative routes. Traffic calming measures include modal filters, a ‘kink’ in the course of the road to deflect site-lines and a central median where road width permits. Level changes, surface treatments (materials, colours, textures), and clear and consistent signage, reinforces the transition into a distinct landscape typology.

Section 01: Broad Fietsstraat with Cambered Median and 'Inritbanden' Ramped Kerb (Author's, 2020).

SECTION 01: BROAD FIETSSTRAAT

Section elevations communicate both functional and technical interventions, and how these proposals are relevant phenomenologically. The bodily disruption inherent to existing pedestrian infrastructure, for example, is addressed with broad, level footways and ‘intritbanden’ (ramped) kerbs. This represents an extension of bodily space that can be effectively incorporated into the ‘lived body’ of users, and particularly those who are mobility impaired (Toombs, 1995).

The inward-looking nature of modernity has resulted in greater physical and emotional distancing between neighbours. Ever-taller, rigid boundaries are bold statements that “this is my property, not yours”—a sentiment echoed by Buttimer (1980:185) who writes: ‘as each individual entrepreneur and his family become more emancipated from former constraints […] they are also deprived of former opportunities to contribute toward the collective sense of place’. Rear gardens are acknowledged as largely beyond intervention, except for where objects and entities interact with the street. Here a fundamental societal shift is required to recognise that any street-facing form (house, tree, boundary etc.) imposes a view—and by extension, a personal, phenomenol response by those who encounter it. This notion is captured by Garrett Eckbo (1950:10) who writes ‘every landscape design [produces] some sort of cumulative effect, good or bad, on those who pass through it’. The resident who fails in the upkeep of their house, for instance, imposes this scene on other landscape users. Failure of upkeep, then, is the superordinate phenomena or ‘background condition’ which makes a personal emotional response possible.

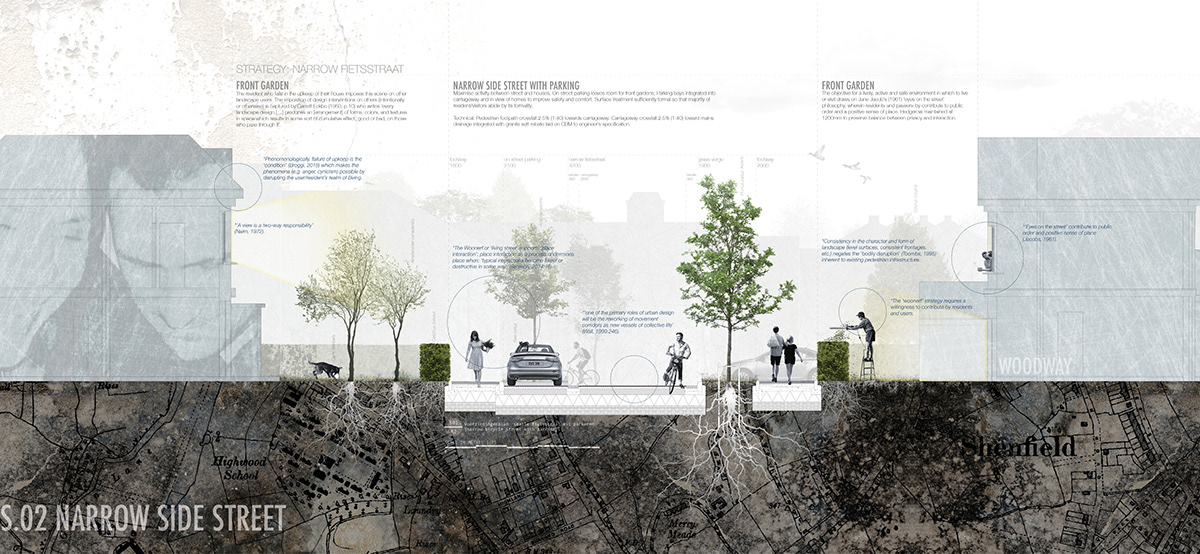

Section 02: Narrow Side Street with On-Street Parking (Author's, 2020).

SECTION 02: NARROW SIDE STREET

The objective for a friendly, active and safe environment in which to live and visit draws on Jane Jacobs’ (1961) ‘eyes on the street’ philosophy, wherein residents and passers-by contribute to public order and a positive sense of place. More broadly, the place processes posited by Seamon (2014) are instructive in understanding how sensitive design can contribute to positive ‘place attachment’, that is, ‘the modes and intensity of emotional bonds with place’ (ibid.:19).

A section elevation through a narrow side street (pictured) demonstrates how the Woonerf and Fietsstraat philosophies can be extended to ancillary roads to activate and sustain these positive emotional bonds. As with the broad Fietsstraat, the carriageway is bounded by a granite sett rebate, but lacks a cambered median. Instead, space is given over to on-street parking, broad pavements and a generous grass verge planted with trees. Integrated parking bays in view of homes improves both the safety and comfort of residents/visitors and creates room for reinstated gardens and hedgerows. Ultimately, the design proposal demands a fundamental cultural shift—from central and local government to the subjects living and immersed in the streets themselves. It nonetheless responds to a sincere and open account of the residential street and a fuller understanding of Being-in-the-world.

THANK YOU

This presentation is a much abridged version of my MA Landscape Architecture thesis The Essence of Landscape: An Enquiry into Phenomenology and the Residential Suburban Street (Writtle University College, 2020).

With kind thanks to J. Gooding and J. Copeland (2020) for use of archive material (postcards), which were adapted in a number of my conceptual and methodological visualisations.

REFERENCES: • Broggi, J.D. (2018) Sacred Language, Sacred World: The Unity of Biblical and Philosophical Hermeneutics. London: T&T Clark. • Buchanan, P. (2012) A Pivotal Point: On the Edge of History. In P. Brislin, ed. Human Experience and Place: Sustaining Identity. Architectural Design Profile. London: Wiley, 136–139. • Buttimer, A. (1980) Home, Reach, and the Sense of Place. In A. Buttimer & D. Seamon, eds. Human Experience of Space and Place. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 166–187. • Eckbo, G. (1950) Landscape for Living. In S. Swaffield, ed. Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 9–11. • Edwards, A.M. (1981) The Design of Suburbia: A Critical Study in Environmental History. London: Pembridge Press. • Finlay, L. (2009) Debating Phenomenological Research Methods. Phenomenology & Practice. 3(1). • Giorgi, A. et al. (2017) The Descriptive Phenomenological Psychological Method. In C. Willig & W. Stainton Rogers, eds. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research In Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 176–192. • Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and Time. Oxford: Blackwell. • Horrigan-Kelly et al. (2016) Understanding the Key Tenets of Heidegger’s Philosophy for Interpretive Phenomenological Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 15(1). • Husserl, E. (2001) Logical investigations. D. Moran, ed. London: Routledge. • Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage. • van Manen, M. (2007) Phenomenology of Practice. Phenomenology & Practice. 1(1), 11–30. • Moran, D. (2014) ‘The Ego as Substrate of Habitualities’: Edmund Husserl’s Phenomenology of the Habitual Self. Phenomenology and Mind. 6, 27. • Nairn, I. (1956) Outrage. London: The Architectural Press. • Relph, E. (2008 [1976]) Place and Placelessness. London: SAGE. • Seamon, D. (1987) Phenomenology and Environment-Behavior Research. In E. H. Zube & G. T. Moore, eds. Advances in Environment, Behavior, and Design. 3–27. • Seamon, D. (2002) Phenomenology, Place, Environment, and Architecture: A Review of the Literature. [online]. At: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238798666 (Accessed 04 Oct 2019). • Seamon, D. (2014) Place Attachment and Phenomenology: The Synergistic Dynamism of Place. In L. Manzo & P. Devine-Wright, eds. Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods, and Applications. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 11–22. • Seamon, D. (2019) Whither Phenomenology? Thirty Years of Environmental and Architectural Phenomenology D. Seamon, ed. Environmental and Architectural Phenomenology. 30(2), 37–45. • Sennett, R. (2018) Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. London: Allen Lane. • Toombs, S.K. (1995) The Lived Experience of Disability. Human Studies. 18(1), 9–23. • Zahavi, D. (2019) Phenomenology: The Basics. London: Routledge.