Part I – The past’s traditional approach to monuments and memorials is no longer relevant and requires a revisit in order to fully realize their potential roles in public spaces.

Monuments and memorials are a frequent sight in public spaces across America. While differing in design and artistic approach, many of these monuments are mono-functional and constructed with permanent materials like bronze, marble, stone and iron. Their permanent structure not only excludes personal expression, but also implies a permanent view, story or sentiment that supports the political agenda of a ruling majority and lacks the ability to accommodate shifting perspectives or future revelations. The past’s selected victim or celebrated hero represented in a figurative design, like the sixty foot tall Confederate War Memorial in Dallas (1896), may no longer be relevant to a community’s current inhabitants, but the visual nature of the edifice suggests a story concluded upon its inauguration.

In modern times, the most structurally relevant features of a community are rarely depicted in its commemorative landmarks, but rather in its commercial architecture. Popular consumer destinations like Wendy’s or Walmart update their logo and remodel their façade nearly every fifteen years in order to accommodate contemporary tastes. Instead of selecting just one customer, these corporations adopt strategies and promote affordable products that actually appeal to the masses.

A close example of this visual neutrality and democratic approach in the realm of monuments and memorials would be the obelisk. Designed nearly three thousand years ago by the Egyptians as temple entrances that typically honored Sun Gods and ruling Pharaohs, these structures have spread throughout the world by means of imperial might and appropriation.[1] Their abstract form, detached from their original context, provides obelisks with the ability to stand in for many historical events; The Washington Monument in Washington D.C. (1885), The Jefferson Davis Monument State Historic site in Kentucky (1917), Abraham Lincoln’s Tomb in Illinois (1874), The Bunker Hill Monument in Massachusetts (1843), etc.

While these monuments prove that a standardized shape is acceptable for honoring many different figures and battles, why is an “official” meaning still necessary? Why do these structures need to be hundreds of feet tall, and constructed with heavy, expensive and permanent materials? Is it possible to embrace the neutrality of their abstraction and increase their functionality?

Part II – A progressive monument adheres to the principles of homomimicry* and exists in multiples; by borrowing features from the surrounding, standardized landscape, an inclusive, interactive design with open meaning is achievable.

A proposed solution to the static role of monuments in public spaces is the implementation of a standardized monument in every city in America; a simplified, recognizable form whose initially undefined meaning and multifunctional mobility generates interpretations dictated by the present community or individual’s actions. Adhering to moods of tradition, spontaneity or convenience, the monument is a calendar object, functioning in between a park bench with a memorial plaque and a larger than life bronze chariot, that instigates contemporary ritualistic behavior and adapts to the desires of a variety of users and their sentiments, both national and local.

A monument in upright position can serve as a dedication to the strength of Vietnam War veterans or as a memorial to the victims of the My Lai Massacre. A monument on its side can represent a deceased celebrity or one’s late grandmother. An unhinged monument can be seen as a symbol of protest – presenting the implied decapitation of a corrupt political leader or a cheating spouse.

In case a monument goes missing or becomes too weathered, a local patron has the ability to provide a community with a new monument by donating a small fee. He or she will be honored accordingly with an embroidered patch.

The monument’s homomimetic approach eases its symbolic allusions and its acceptance in to the standardized landscape. Its low cost, efficient manufacturability and material qualities, including both fire and water resistance, are features designed intentionally to compliment its surrounding family of expected standardized objects, such as the park bench, fire hydrant, picnic table, street light, etc., as well as their expected interactions.

Textures, rendering and animation by Joanna Lin

Part III – The utilization of proper media that naturally appeals to American culture will generate national acceptance of and stem interactions with the monument.

However, based on previous models of the systematic integration of new tools and technologies in to an expansive location, it is often challenging for each community to fully adopt the object and gain long term benefits from its intended potential. In the case of One Laptop Per Child, an ambitious attempt to distribute low cost laptops to children in developing nations in order to improve education and technological literacy, the operation failed, among other reasons, due to its inability to properly penetrate the intended populations through an appropriate form that catered to the consumer’s culture.[2]

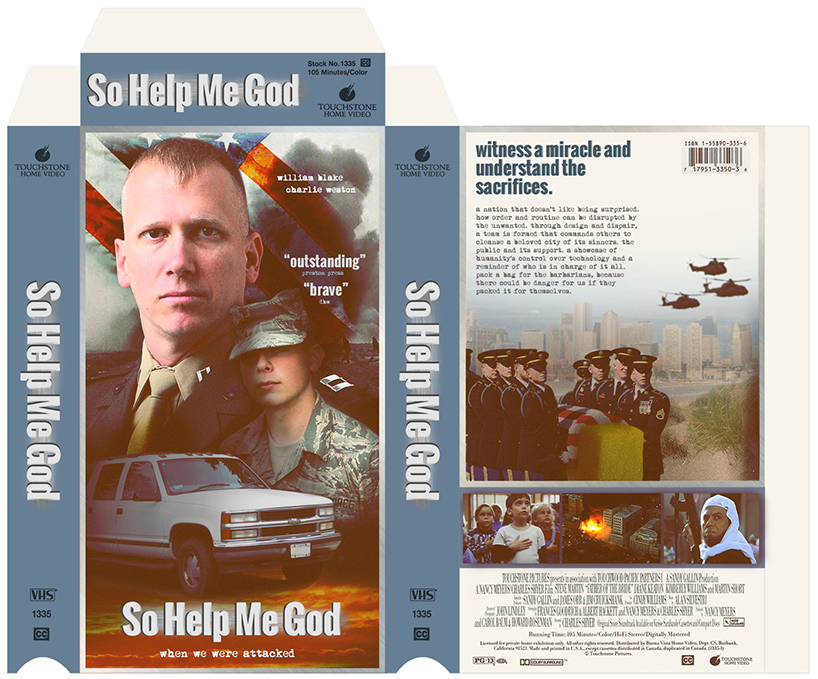

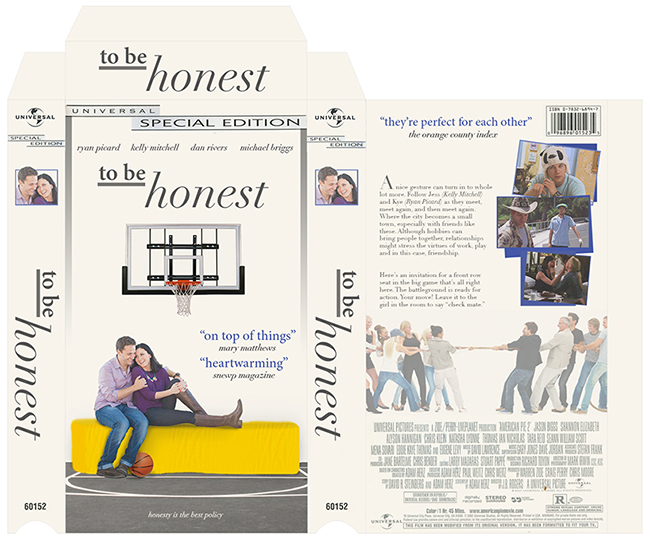

This will likely not be an issue for the monument in America due to the effective influence of Hollywood and its consistent nature of featuring and exploiting generic, popular, commonly experienced and nationally relevant phenomenon.

Films have, historically, both directly and indirectly impacted mainstream culture, behavior and expectations. A direct example being the Harvard Alcohol Project, that, in order to reduce alcohol-related traffic fatalities, normalized the role of the “designated driver” to young adults through popular movies and TV series in the 1990s.[3]

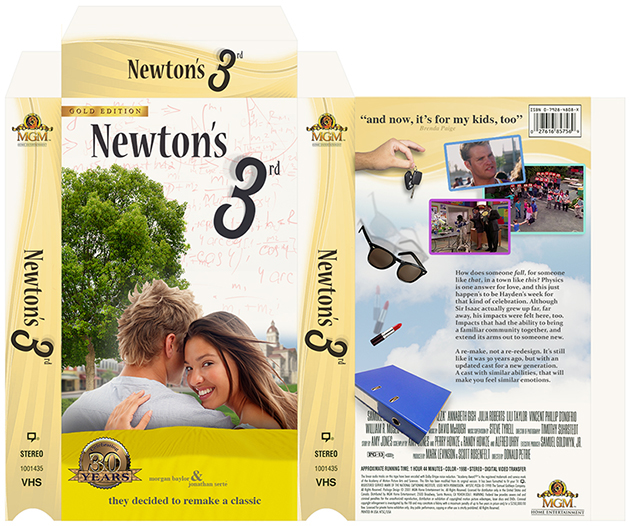

On the other hand, the monument and its journey in to an accepted collective conscious will be realized indirectly. Losing one’s virginity at a high school prom, the wacky behavior of families during Christmas and the zany happenings on a road trip are just a few examples of common tropes without a social agenda that, having been featured in films so frequently, we have come to expect and are willing to perform when faced with such experiences in reality.

Closer to our argument here, we are more interested in the monotonous inclusion of standardized objects and their imposed behaviors in film. Objects that are not as seasonal as the events listed before. Objects that are not as exclusive as props turned commodities like Jules Winnfield’s Bad Motherfucker wallet (Pulp Fiction, 1994) or Marty McFly’s Nike Air Mag sneakers (Back to the Future Part II, 1989). Objects that exist 365 days per year, in every city in the country, accessible to any individual. Objects that, after being featured in countless films with corresponding interactions and narratives, become props with actions easily replicated in reality.

While Forrest Gump (1994) does present the functionality of a park bench as a tool for seating multiple individuals waiting for a bus, it also presents the possibility for the park bench to function as a prop that instigates the telling of a stranger’s fantastical life story. While the opening of Friends(1994-2004) does present the function of a public fountain as a beautiful object to observe at night, it also presents the possibility to jump in to a fountain and actively dance in the water with one’s own friends.

While the film Grease (1978) features a 1948 Ford De Luxe ‘Grease Lightening’, high school theater adaptations feature a simplified, cardboard version of the infamous automobile.

These activities may have either been actually experienced or imagined by only a few individuals, but they are used simply as strategic devices that utilize familiar objects to drive stories on screen. Coincidentally, these stories eventually have the ability to transgress in to reality, building the expectations of individuals when they encounter props from “fictional” worlds in their own surroundings, thus driving the performative qualities these objects possess and furthering the city’s assumed role as a spectacle.

While there will be communities who do form their own uses, meanings and experiences with their local monument, others without direct understanding will presumably conform to narratives, behaviors and interactions based on what is continuously visualized on screen, thus effectively maximizing the functional and narrative potential theorized during the prop’s conception.

* Homomimicry is an approach to innovation that seeks sustainable solutions to human challenges by emulating humanity’s time-tested patterns and strategies. The goal is to create products, processes and policies – new ways of living – that are well adapted to life on earth over the long haul.

Notes

1. Brian A. Curran, Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, Benjamin Weiss, Obelisk A History (Cambridge: The Burndy Library, 2009)

2. Shah, Namank. “A Blurry Vision: Reconsidering the Failure of the One Laptop Per Child Initiative” BU.edu. Boston University Arts & Sciences, n.d. Web. 28 April 2015.

3. “Harvard Alcohol Project.” hsph.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College, n.d. Web. 1 May 2015.

Thank you; Mitch Froelich, Andy Law, Joanna Lin, Soojung Ham, Emily Hoffman, Michael Savoia, Nick Scappaticci, Nathaniel Smith, Seth Stem